The days of Americans sticking with one employer for life and ending up with a gold watch are long gone.

Baby boomers are retiring — and people are quitting their jobs — more frequently than ever.

Current trends notwithstanding, sooner or later, every employee leaves.

Smart organizations know that the inevitability of employee turnover doesn’t have to mean people take their hard-won wisdom, insight, and knowledge with them when they go.

Most successful businesses have codified the nuts and bolts of operations into their training programs and SOPs. This information is sometimes called explicit knowledge.

But some knowledge is much more difficult to capture and pass on. That’s the unwritten understanding and insight that employees accrue with experience, and too often, organizations let it walk out the door.

In management theory, this is called tacit knowledge — defined as “skills, ideas, and experiences that are possessed by people but are not codified and may not necessarily be easily expressed.”

This article will look at the causes of lost tacit knowledge and its costs — and how organizations can prevent squandering this precious resource.

What Are the Causes of Lost Knowledge?

Organizations fail to retain valuable expertise and tacit knowledge for numerous reasons.

The most obvious occurs when employees leave — either through retirement or pursuing a new opportunity — without passing on the knowledge and insights gained through experience.

We’ve identified three primary causes of lost knowledge likely to affect every employer — regardless of industry specialization.

Knowledge Hoarding

Any employee and manager that’s been in the workforce for a reasonable length of time will have encountered a knowledge hoarder.

Knowledge hoarding is the practice of employees consciously — or even subconsciously — failing to share information and insights with colleagues. Often, it’s tacit information accumulated through experience that long-tenured employees are most unwilling — or unable — to share.

Harvard Business Review refers to this type of knowledge as deep smarts.

According to HBR: “[Deep smarts] may be technical, but they can also be managerial, as when an experienced manager has hard-earned skills in problem identification and solution, crucial relationships with customers, or a detailed understanding of how to innovate.”

All skills that any organization can ill afford to lose.

Here are five of the most common reasons and motivations behind knowledge hoarding:

- Personal gain: Retiring employees or managers may see an opportunity to be hired back as a consultant to do the same job they’ve always done but with double pay.

- Fear of losing status: Everyone likes to be appreciated. For some people, being the “go-to” person on a team is integral to their feelings of self-worth. They may feel that their stature within the organization — and how their colleagues perceive them — will be diminished if they share the tacit knowledge undergirding their expertise.</li style=”padding-bottom: 16px;” >

- Internal competition: Some organizations and managers like to pit individuals or teams against each other within the company. They may feel that “healthy competition” will increase productivity, innovation, or performance. That may sometimes be the case, but it’s easy to see how internal competition can lead to a reluctance to share knowledge that people perceive as advantageous to themselves or their team.

- Lack of trust or acknowledgment: People who fear that knowledge they pass on may be undervalued or misused are less likely to share it. According to The 7 Fundamentals to Create and Sustain A Successful Knowledge Sharing Organization, “To encourage employees to share the knowledge gained through experience requires building trust and an understanding of how their knowledge will be used.”

- Resentment: Employees retiring or taking another job may feel that they “don’t owe it” to the organization to pass on tacit knowledge before they leave. People who felt underappreciated or undervalued during their time with the company — particularly those who harbor resentment — are far less likely to share their tacit knowledge voluntarily.

- Lack of time or resources: Employees may simply be too busy to pass on their valuable tacit knowledge. Or they may lack effective tools to codify and share it. It’s up to the organization to ensure that time and resources are not obstacles to transferring knowledge.

Whether it’s done intentionally or not, knowledge hoarding almost inevitably leads to knowledge lost.

The Silver Tsunami

The silver (or gray) tsunami refers to an aging population. In business, it’s frequently used to describe the ongoing exodus of baby boomers from the workforce.

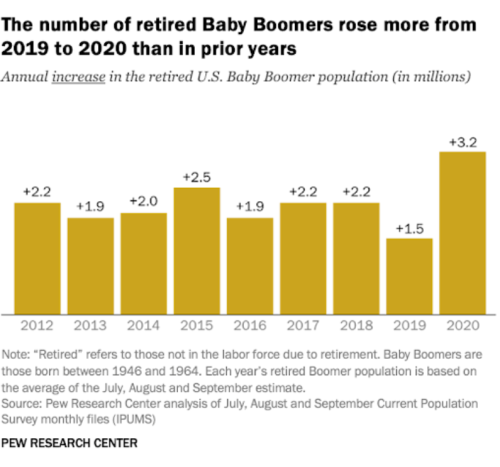

The prediction of a baby boomer time bomb dates back to at least the late 1990s. Many publications, government reports, and academic papers have identified the enormous challenge the retirement of the generation born between 1946 and 1964 presents for employers.

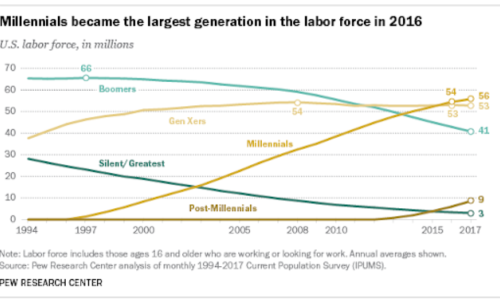

The pace of baby boomers leaving the workforce has only accelerated in the past few years. In the third quarter of 2020, the number of boomers retiring increased by 3.2 million over the same quarter in 2019.

How Does the Silver Tsunami Impact Knowledge Loss

According to Dr. David DeLong, author of Lost Knowledge: Confronting the Threat of an Aging Workforce: “There is little question that many experienced workers will be leaving their jobs in the next decade. And that giant sucking sound you will hear is all the knowledge being drained out of organizations by retirement and other forms of turnover.”

One of the most significant challenges in preventing knowledge loss is that employers often don’t know how integral tacit knowledge is to their organization’s success until it’s gone.

However, the silver tsunami is far from an unforeseen event. It may be happening more quickly than anticipated, but it’s a demographic inevitability. By 2030, all baby boomers will be 65 or older.

It’s incumbent on leadership to ensure that as much tacit knowledge and experience as possible passes from aging workers to the next generations of employees.

The Great Resignation

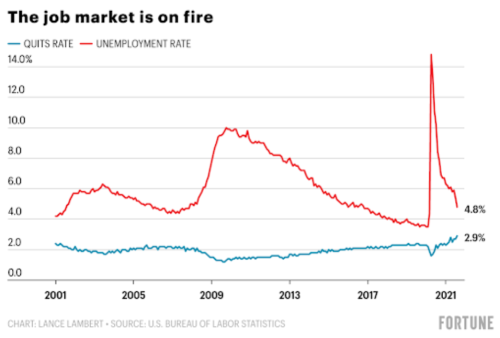

The Great Resignation — also referred to as the quitting economy and the Big Quit — is an ongoing phenomenon that began in spring 2021. It refers to the record numbers of employees voluntarily leaving their jobs in the US.

In September 2021, 4.4 million people quit their jobs. That number represents 3% of America’s workforce, a 2% increase over the previous month, and a 22% increase over pre-pandemic levels.

The Great Resignation is such a recent, ongoing phenomenon that its root causes are the subject of much speculation. Some of the most commonly invoked reasons include:

- A tight labor market has resulted in more opportunities for workers. People may feel more confident about the ability to find a better job. For example, a position that pays more; has more opportunities for advancement; offers more benefits like insurance and flexible work, etc.

- The pandemic led many people to question their relationship with work and how it impacts their day-to-day lives. Workers are reevaluating whether their current position (or career) is personally fulfilling and if it furthers their long-term life goals.

- A younger workforce: The largest worker demographic is now millennials, with Gen Z predicted to comprise 27% of the workforce by 2025. Millennials and Gen-Z have different attitudes to work and expect a better work/life balance than previous generations. According to a recent report by Adobe, “at least half of enterprise workers would switch jobs for more work/life balance, to be more in control of their schedules, or to be able to work remotely — especially Gen Z and millennials.”

Additionally, “more than a third of the workforce — and half of Gen Z — plan to switch jobs in the next year.”

How Does the Great Resignation Impact Knowledge Loss?

The younger the employee, the less likely they are to have accumulated valuable institutional knowledge outside of a company’s existing onboarding and training protocols.

Losing an employee that’s only been with the company for a few years (or months) is unlikely to result in much loss of tacit knowledge within the organization. However, new employees are also the most likely to benefit from the wisdom and experience of long-tenured staff.

Crystallizing tacit knowledge within the organization, incorporating it into training, and making it a fundamental part of company culture are some of the best ways to fast-track a new team member’s success.

Gen Z workers may be more likely to switch jobs than other demographics, but they’re far from the only people quitting. As discussed above, people are retiring faster than ever. Gen X and millennials are also switching jobs or leaving the workforce in greater numbers and are old enough to have accumulated significant amounts of tacit knowledge in companies they’ve worked in for years.

It’s crucial for organizations to have a process for capturing knowledge that could be lost in an era of high employee turnover. It’s also vital for companies to use the best tools to pass that accumulated knowledge and experience on to younger hires.

What are the Costs of Lost Knowledge?

A 2018 study estimated that “the average US business loses $47 million in productivity each year due to inefficient knowledge sharing.”

The same study found that “42 percent of institutional knowledge is acquired specifically for the employee’s current role and is not shared by any of their coworkers. When that employee leaves their job or is otherwise unavailable, their coworkers are unable to do 42 percent of that job.”

Additionally, “60 percent of respondents found it difficult, very difficult, or nearly impossible to obtain information vital to their job from their colleagues.”

According to an International Data Corp. (IDC) study, “Fortune 500 companies lose at least $31.5 billion a year by failing to share knowledge.”

In a 2017 Harvard Business Review article referencing the IDC study, Christopher G. Myers warns: “By trying to recreate the wheel, repeating others’ mistakes, or wasting time searching for specialized information or expertise, employees incur productivity costs and opportunity costs for the organization.

Formal systems might help communicate established best practices, but they often don’t explain how an individual should apply them to their own work.”

Though researchers have tried, it’s hard to put a finite price tag on the cost of lost knowledge and experience. It will vary widely across each industry and within each organization.

For some companies, much of their operations can easily be broken down into repeatable processes and documented. But as AI and automation take over more and more menial tasks, capturing human experience and tacit knowledge is likely to grow even more crucial for organizations to remain competitive in future.

Why Is Tacit Knowledge So Difficult to Capture and Pass On?

In 1991, Japanese organizational theorist Ikujiro Nonaka published a highly influential article in Harvard Business Review.

The article “helped popularize the notion of ‘tacit’ knowledge—the valuable and highly subjective insights and intuitions that are difficult to capture and share because people carry them in their heads.”

Nonaka argued that traditional Western management practices failed to value tacit knowledge, instead believing that “the only useful knowledge is formal and systematic—hard (read: quantifiable) data, codified procedures, universal principles.”

According to Nonaka, innovation “depends on tapping the tacit and often highly subjective insights, intuitions, and hunches of individual employees and making those insights available for testing and use by the company as a whole.”

The challenge is that “Tacit knowledge is highly personal. It is hard to formalize and, therefore, difficult to communicate to others. To convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge means finding a way to express the inexpressible.”

Nonaka tells the story of how the Research and Development team at Matsushita, the parent company behind home-name consumer electronics brands like Panasonic and JVC, struggled to develop a bread-making machine.

No matter how hard they tried, they were unable to build a machine that could knead the dough correctly. The end result was always bread overcooked on the outside and almost raw on the inside. Engineers analyzed the dough extensively and could find no difference between what the machine produced — which was basically inedible — and the dough kneaded by professional bakers, which emerged from the oven perfectly cooked.

The R&D team was stymied by these results until Ikuko Tanaka, a Matsushita software engineer, came up with a creative solution. The Osaka International Hotel was renowned for making Osaka’s best bread. Tanaka arranged to apprentice with the hotel’s head baker to study his technique for kneading dough.

Through close observation and learning to make the bread herself, she discovered the baker had a distinctive method of stretching the dough by hand. This technique was something the baker had learned through experience and that Matushita’s engineers had previously failed to capture. The baker may not even have been consciously aware of it himself.

Using the head baker’s tacit knowledge that Tanaka successfully captured through watching and doing, she and Matsushita’s engineers developed a product that successfully employed the same techniques. The “twist dough” method resulted in record-setting sales of a new kitchen appliance.

This story illustrates the elusive nature of tacit knowledge. As Nonaka puts it: “A master craftsman after years of experience develops a wealth of expertise ‘at his fingertips.’ But he is often unable to articulate the scientific or technical principles behind what he knows.”

This observation applies to virtually any successful member of an organization who has accumulated valuable tacit knowledge through experience.

So what can companies do about it?

How Can Companies Prevent Lost Knowledge?

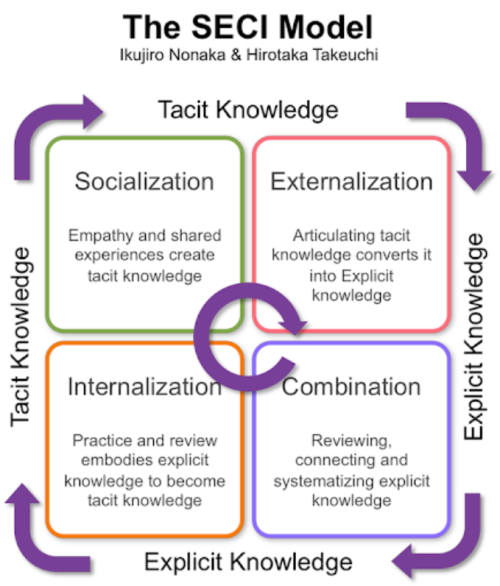

Nonaka identified four basic principles for capturing tacit knowledge and creating new knowledge and innovation within an organization.

- Tacit to Tacit knowledge transfer takes place when one member of the organization shares information directly with another. Mentoring and coaching are examples of this type of knowledge transfer (socialization).

- Tacit to Explicit knowledge transfer happens when an individual is able to codify or record their tacit knowledge and share it with others. Examples include writing it down or creating video training materials that make it more practical to share knowledge within an organization combination (externalization).

- Explicit to Explicit knowledge creation occurs when an individual combines distinct sources of explicit knowledge to create a new understanding of the organization. A typical example of this is a financial report, which gives employees and managers an overview of the company’s position, the efficiency of its operations, and the success of its initiatives (combination).

- Explicit to Tacit knowledge creation happens when team members assimilate explicit knowledge and use it to inform and extend their own tacit knowledge of how to effectively achieve their goals (internalization).

Nonaka asserts that in a knowledge-creating company — one inherently less prone to lost knowledge — “all four of these patterns exist in dynamic interaction, a kind of spiral of knowledge.”

Practical Steps Businesses Can Take to Minimize Lost Knowledge

Now that we have a basic understanding of the prevalent theories behind managing tacit knowledge and maximizing its benefits, what are some practical ways organizations can minimize lost knowledge?

Incentivizing Knowledge Transfer

Knowledge management research has shown that companies can effectively encourage individuals to share tacit knowledge within the organization through incentivizing knowledge transfer.

But it’s crucial to approach rewarding knowledge transfer in the right ways — otherwise, such measures may have the opposite of the intended effect.

One influential study suggests that team-based financial and non-financial incentives have the most beneficial impacts on encouraging knowledge sharing.

Team-Based Financial Incentives for Knowledge Transfer

Financial incentives — like bonuses and stock options — are often offered to individuals to encourage better performance. Tangible individual incentives may motivate people to work harder, but numerous studies have shown that they can actually have a negative effect on knowledge sharing.

One such study suggested that “incentive contracts might undermine voluntary cooperation, and the undermining was so strong that the incentive contracts were less efficient than contracts without any incentive.”

Another found that tangible rewards targeted at individuals diminish the motivation to share knowledge: “The more employees perceive knowledge sharing to lead to tangible rewards, the less they are autonomously motivated to share.”

On the other hand, team-based incentives “ties an individual’s compensation to the overall performance of the organization.” Team-based incentives have the additional benefit of “achieving joint involvement and commitment.” By shifting the focus from “individual performance to collective outcomes,” group-based incentives encourage individuals to share their tacit knowledge and expertise for the benefit of the team and the organization at large.

Compared to individual economic incentives, team-based rewards are “a more trustworthy method for firms to motivate sustained cooperation and improve interpersonal trust,” leading to more knowledge sharing, better knowledge management, and less lost knowledge.

Non-Financial Knowledge Sharing Incentives

Money is far from the only way to motivate individuals to share their knowledge. One study outlined numerous non-financial incentives that encourage self-directed individual performance, including:

- Individual interests

- Praise

- Constructive feedback

- Challenging work

Most successful individuals are intrinsically motivated to “be curious and interested, to seek out challenges, and to exercise and develop their skills and knowledge, even in the absence of [financial] rewards.”

By building a harmonious organizational culture that rewards knowledge transfer and collaboration, leadership encourages voluntary knowledge sharing, builds team cohesion, and reduces lost knowledge.

Mentorship

In Nonaka’s example above, one of Japan’s most prominent consumer electronics manufacturers repeatedly failed to develop a commercial bread maker. They only succeeded after a software engineer came up with the idea of apprenticing with a master baker to learn his “secrets” — or tacit knowledge.

Although mentoring or apprenticeships can be time-consuming, they remain among the best ways for experienced members of an organization to pass on their wisdom, experience, and tacit knowledge.

Traditionally, mentoring has taken place primarily in person. But the ongoing shift to remote and hybrid work has made mentorship more challenging — and arguably even more crucial.

As Gen-Z enters the workforce — and baby boomers leave — in ever-increasing numbers, transferring tacit knowledge should be a priority for any organization to future-proof their success.

According to a recent Harvard Business Review article on mentorship in a hybrid workplace:

“For early-career employees… how does one learn best practices to succeed in one’s career when you’re working alone from home? How does one build the professional relationships that are critical for survival and advancement?”

The authors go on to identify several elements of a successful mentorship program for hybrid or remote work. Many of the principles also apply to mentorship in traditional workplace environments.

- Build and nurture meaningful one-on-one relationships: Despite attempts by many companies to “scale up” mentorship and team-building through virtual social events, “many people report fatigue around virtual group events.” Building authentic connections between individuals also builds mutual trust and genuine care. Long-tenured members of an organization are far more likely to share tacit knowledge with someone they feel an authentic connection with.

- Embrace the potential of remote collaboration: It’s often said that there’s no substitute for meeting face-to-face. While face-to-face mentoring does have some advantages, mentorship and sharing tacit knowledge through tools like Zoom and Slack also has upsides. One of the most apparent is enabling organizations to facilitate the best match between mentors and mentees without regard to geographical proximity.

- Take a holistic approach: Many workers have embraced the freedoms offered by remote and hybrid work. But the lack of structure and social interaction that a traditional workplace can provide has also had negative impacts — particularly on young people. A recent University of Miami study shows that the Covid-19 pandemic produced increased feelings of loneliness in 65% of respondents, while 80% of participants (aged 18-35) reported experiencing “significant depressive symptoms.”

Encouraging mentors and mentees to discuss matters outside of work can help build trust and connection that facilitates the transfer of knowledge. Not only that, according to the HBR article: “Mentoring can help us stay resilient and connected in the face of challenges [like the pandemic]. Acknowledging how much our personal and professional lives are intersecting is a powerful basis for any mentoring relationship.”

Leverage Next-Generation Learning and Development and Coaching Technology

Even people whose primary role is to pass on tacit knowledge — think athletic coaches, subject matter experts (SMEs), and line managers — struggle to do so without the right tools.

Finding the time and technology best suited to capturing, codifying, and sharing tacit knowledge is an enormous challenge in its own right.

Microlearning platforms like Learn to Win can offer a significant competitive advantage for organizations looking to unlock the job-specific operational knowledge that distinguishes their top performers.

Learn to Win’s software unlocks the untapped expertise in every organization by gamifying the Last Mile of learning: the critical operational and tacit knowledge that drives performance — but is rarely taught.

Learn to Win’s diverse range of clients includes the US Department of Defense; sports teams like the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins and Ole Miss football; and Fortune 500 companies, such as Chick-fil-A, Novartis, and Regeneron.

The platform eliminates the friction of tacit knowledge transfer for coaches, mentors, senior managers, and employees. It’s quick and intuitive to create completely customized lessons and learning materials — even for people who are technology-averse.

By gamifying the knowledge transfer process and utilizing the latest cognitive and learning science principles, Learn to Win makes it easy and enjoyable for people to absorb tacit knowledge in bite-sized chunks: On their own schedule and on any smartphone, computer, or tablet device.

For organizations that have minimized or eliminated the many other barriers to tacit knowledge transfer and need a platform to get their team over the final hurdle — and prevent lost knowledge — Learn to Win can be a gamechanger.

Final Thoughts

Knowledge is power. Tacit knowledge can take years (or decades) to accumulate, but as long as it resides solely with an individual, organizations can lose it in a heartbeat.

Given the proper tools, support, and incentives, most individuals in an organization will likely be happy to codify and share as much of their tacit knowledge and wisdom as possible.

It’s incumbent on leadership to provide a robust framework for knowledge transfer and management — and minimize the enormous opportunity and financial costs of lost knowledge.